Informations diverses - Diverse information

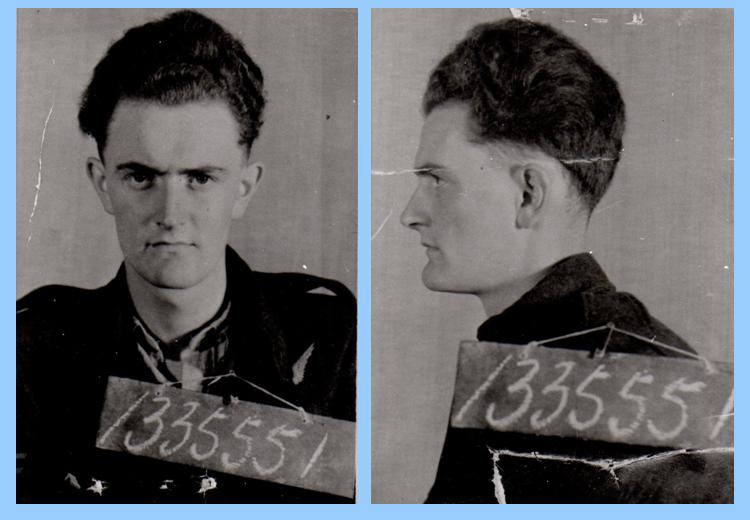

* Le Sergent Keirle fut projeté de l'avion, lors de l'impact avec le sol. Atteint à la colonne verticale et à la jambe gauche, il fut secouru par un soldat allemand arrivé sur place et qui

appela une assistance médicale.

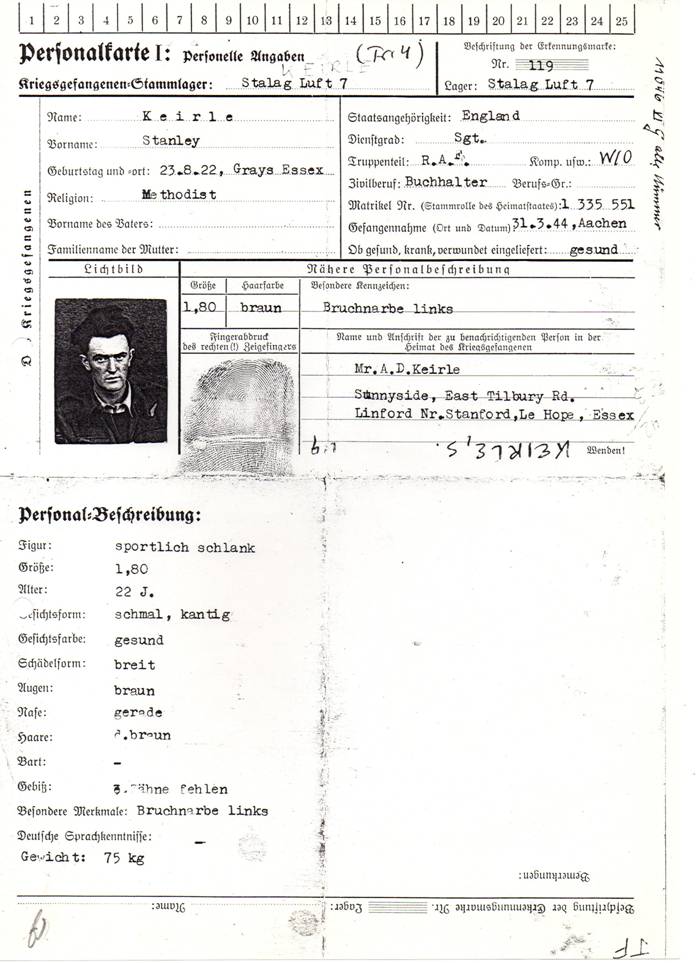

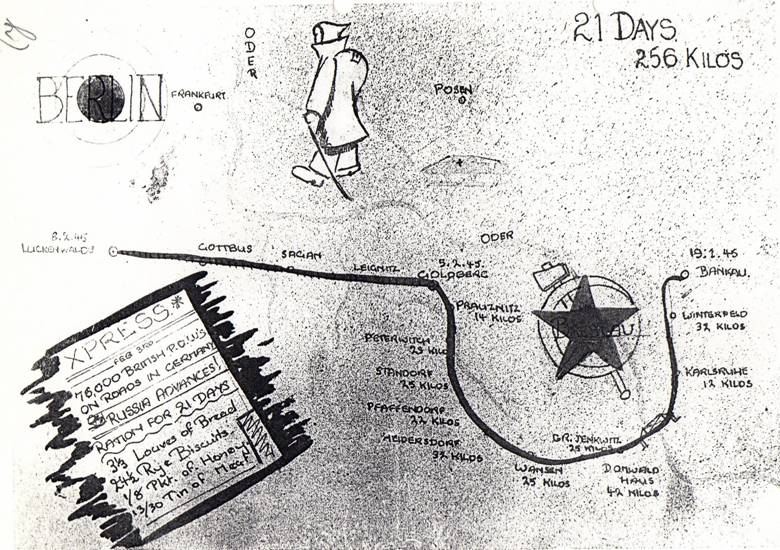

Après les soins et sa réhabilitation, il fut fait prisonnier de guerre comme les Sergents Jeffrey et Upton, également survivants du drame. Il fut emmené au camp de Bankau. Lors de l'avancée des Russes, en janvier 1945, il fut rejoint par

une foule dautres prisonniers pour commencer la longue marche qui les firent quitter Bankau dans la neige et le froid et parcourir des distances énormes, dans le but d'être soustraits aux Russes.

Ses blessures l'empêchèrent d'avancer normalement, tant il souffrait. Sur l'ordre du médecin du camp, il fut envoyé avec d'autre prisonniers également blessé, vers le camp de Luckenwalde. On présume qu'il

est arrivé à la base de la RAF, à Benson (South Oxfordshire, UK) entre le 8 et le 11 mai 1945.

Le père de James Whitley, J.E. Whitley, qui était Capitaine des « Royal Engineers » a reçu après la guerre une lettre du sergent Keirle, dans laquelle, l'opérateur radio expliquait ce qui s'était passé:

"Le sergent Keirle se rappelle encore du briefing habituel de mars 1944. « L’objectif était Nürnberg. Nous avons décollé vers 21h30 et tout semblait calme jusqu’à ce que nous approchâmes la côte où l’ennemi se trouvait. Nous apercevions les feux des projecteurs de l’ennemi, mais nous avons réussi à les esquiver. Jimmy avait aperçu un chasseur et nous avons alors effectué les manœuvres courantes d’évasion. Le chasseur ne nous a pas attaqués, mais continua à voler en-dessous de nous. Durant ce vol, j’ai éteint l’intercom pour écouter l’émission de minuit de la base.

Deux minutes plus tard, j’ai senti un choc. J’ai immédiatement remis l’intercom, juste à temps pour entendre le mitrailleur de dessus (Upton) m’informer que le moteur à bâbord extérieur et l’aile étaient en feu. Le commandant (Jefferies) nous a donné l’ordre de nous préparer à sauter. Après avoir attaché mon parachute, j’ai ouvert la porte et vu que Jimmy Whitley et George Upton avaient également endossé leur parachute. Ensuite, le bombardier (Jeffrey) nous informa que les bombes ne voulaient pas se détacher.

Après j’ai appris qu’il avait tout de même réussi à jeter les bombes. Je me trouvais à ce moment dans la coupole du mitrailleur et je voyais que le moteur extérieur et la moitié de l’aile se déchiraient. Le pilote ordonna immédiatement une sortie de secours et ajouta qu’il ne parvenait plus à tenir l’avion sous contrôle.

L’appareil glissait vers bâbord et perdait de l’altitude. Nous étions piégés et ne pouvions rien faire à cause de la force de traction énorme provoquée par l’aile droite endommagée. Je perdis connaissance, tout comme le bombardier et le mitrailleur de dessus. Je me rappelle vaguement que je tirais à la corde de mon parachute mais que je n’ai repris connaissance qu’après avoir touché brutalement le sol. Je me suis rendu compte que je tenais en main un morceau de l’avion, le dôme du cockpit. J’ai eu des difficultés à me dégager de mon harnais et de ma veste de sauvetage, ainsi que des pièces de l’épave qui m’entouraient.

Je ne parvenais pas à me tenir debout. Après quelques heures, des soldats allemands m’ont repéré et sont restés près de moi jusqu’au matin. Un officier est venu m’interroger sur l’opération que je menais, l’escadron, etc. mais je lui ai fait savoir que je ne le comprenais pas. Après, j’ai voyagé à bord d’un sidecar d’une moto, ce qui allait être le voyage où j’ai le plus souffert et le plus rude de mon existence. On m’a déposé dans un coin près d’un pont.

Plus tard, j’ai été rejoint par le bombardier Jeffrey et le mitrailleur de dessus Upton, les seuls rescapés de l‘avion. Nous avons été amenés dans un hôpital pour prisonniers de guerre à Aix-la-Chapelle. J’y suis resté tandis que les deux autres garçons, qui n’étaient pas blessés, ont été envoyés dans un Stalag. J’avais la colonne verticale brisée, la cheville gauche fracturée, la rate déchirée, une blessure au genou gauche et diverses contusions et coupures.

Je suis resté à l’hôpital d’Aix-la-Chapelle jusqu’au soir du 11 avril quand le RAF attaquait la station avoisinante. L’hôpital a été touché et je suis resté plusieurs heures sous les décombres. J’ai ensuite été amené à Bonn où j’ai pu, après 2 semaines, entrer en contact avec deux anglais. J’ai pu quitter l’hôpital fin juin, pas entièrement guéri mais trop valide pour occuper un lit allemand. On m’a envoyé dans un centre d’interrogation à Frankfurt et puis à Stalag Luft 7 jusqu’au 19 janvier 1945.

Ce jour, nous marchions vers l’Allemagne, loin des Russes. Nous avions parcouru 550 km en un mois et vivions de ce que nous trouvions ou rassemblions sur place. Finalement,

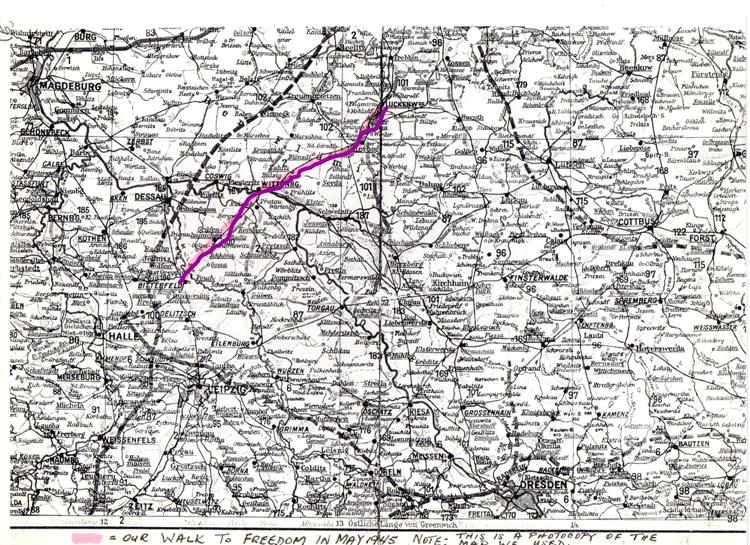

nous sommes arrivés à Stalag 3A, à 50 km au sud-est de Berlin. Nous y sommes restés jusqu’au 6 avril, date à laquelle des Russes nous ont délivrés. Les difficultés n’étaient pas terminées pour

autant, car les Russes nous ont obligés à combattre avec eux pour délivrer Berlin. Comme tout le monde refusait, ils nous ont laissé sans nourriture et dans un camp surveillé par des gardes armés.

J’ai pu me sauver une semaine plus tard, ensemble avec 4 autres soldats. Nous cherchions une route vers les lignes américaines à Bitterfeld. Les américains nous ont ramenés de Leipzig à Reims à

bord de Dakotas, nous ont fourni des uniformes américains et renvoyés en Angleterre à bord d’un Lancaster. Le 19 mai j’étais de retour à la maison où j’apprenais la mort de mon père durant mon

absence.»

* Sgt. Keirle was blown from the plane sustaining injuries to his spine and left leg and found by a German soldier who obtained medical assistance for him.

After care, he was done PoW, as Sgt. Jeffrey and Sgt. Upton, survivors as him. Stanley Keirle was taken to Bankau, with the Russian advancement on January 19th 1945

joined the many POW’s beginning the long march from the camp in heavy snow. Owing to his injuries walking was very difficult and he got detached from the main Bankau group, his injuries

preventing him from keeping up and was diverted to Sagan by the medical officer. From there he and others were sent to Luckenwalde by goods train the following day. He is believed to have arrived at

R.A.F. Benson between the eighth and eleventh of May 1945.

The father of James Whitley, J.E. Whitley, who was captain of "Royal Engineers”. After the war, he received a letter of sergeant Keirle, in witch the wireless-Operator explained what happened.

Sergeant Keirle still remembers himself of the usual briefing of March, 1944. The target was Nurnberg. We took off at about 9:30 pm and everything seemed quiet until we approached the coast where the enemy was. We perceived the spotlights of the enemy, but we had managed to avoid them. Jimmy had perceived a fighter and we had then made the current operations of escape. The fighter did not attack us, but continued to fly below us. During this flight, I switched off the intercom to listen to the broadcast of midnight of the base.

Two minutes later, I felt shock. I immediately put back the intercom, just in time to hear the mid-up air gunner to inform me that the engine on the outside right and the wing were on fire. The pilot gave us the order to prepare us to jump. Having attached my parachute, I opened the door and saw that Jimmy and George had also their parachute on them. Then, the bomber informed us that bombs did not want to get loose.

Later I learnt that he had succeeded in dropping all the bombs. I was at this moment in the mid-up turret and I saw that the outside engine and half of the wing tore. The pilot ordered immediately an emergency exit and added that he did not any more succeed in holding the plane under control.

The aircraft slid towards right and lost of the height. We were trapped and could make nothing because of the strength of enormous drive provoked by the damaged right-wing. I lost consciousness, just like the bomber and the mid-up gunner. I remember myself vaguely that I fired in the rope of my parachute, but that I regained consciousness only having touched brutally the ground. I realized that I held a piece of the plane, the dome of the cockpit. I had difficulty releasing me of my harness and my jacket of rescue, as well as of parts of the wreck which surrounded me

I did not succeed in standing. After a few hours, German soldiers spotted me and stayed near me until morning. An officer came to question me about the operation that I led, the squadron, etc., but I let him know that I did not understand him. Then, I travelled aboard the sidecar of a motorcycle, what was going to be the journey where I suffered the most and the roughest of my existence. They laid me in a place, near a bridge.

Later, I was joined by the bomber Jeffrey and the mid-up air gunner Upton, the only survivors of the plane. We were brought in a hospital for war prisoners in Aachen. I stayed there whereas two other boys, who were not hurt, were sent to a Stalag. I had the broken vertical column, the broken left ankle, the torn spleen, a wound in the left knee and diverse bruises and cuts.

I stayed in the hospital of Aachen until the evening of April 11th when RAF attacked the neighbouring station. The hospital was touched and I stayed several hours under rubble. I was then brought in Bonn where I was able, after two weeks, to get in touch with two English. I was able to leave the hospital at the end of June, was not completely cured but too valid to occupy a German bed. They sent me to a center of interrogation to Frankfurt and then to Stalag Luft 7 until January 19th, 1945.

This day, we walked towards Germany, far from the Russians. We had traveled 550 km in one month and lived on what we found or collected on the spot. Finally, we arrived at Stalag 3A, at 50 km in the southeast of Berlin. We stayed until April 6th, the date in which the Russians freed us. The difficulties were not ended for all that because the Russians obliged us to fight with them to deliver Berlin. As everybody refused, they left with us without food and in a camp watched by armed guards. I was able to save myself one week later, together with four other soldiers. We looked for a road towards the American lines to Bitterfeld.

The Americans returned us of Leipzig to Reims aboard Dakotas, supplied us uniforms American and sent back in England aboard Lancaster. On May 19th I was back home where I learnt the death of my father during my absence.

Source: Goovaerts Wim; Avro Manchester en Avro Lancaster verliezen in België, 1941-1945; Tome 3; De Krijger, 2005